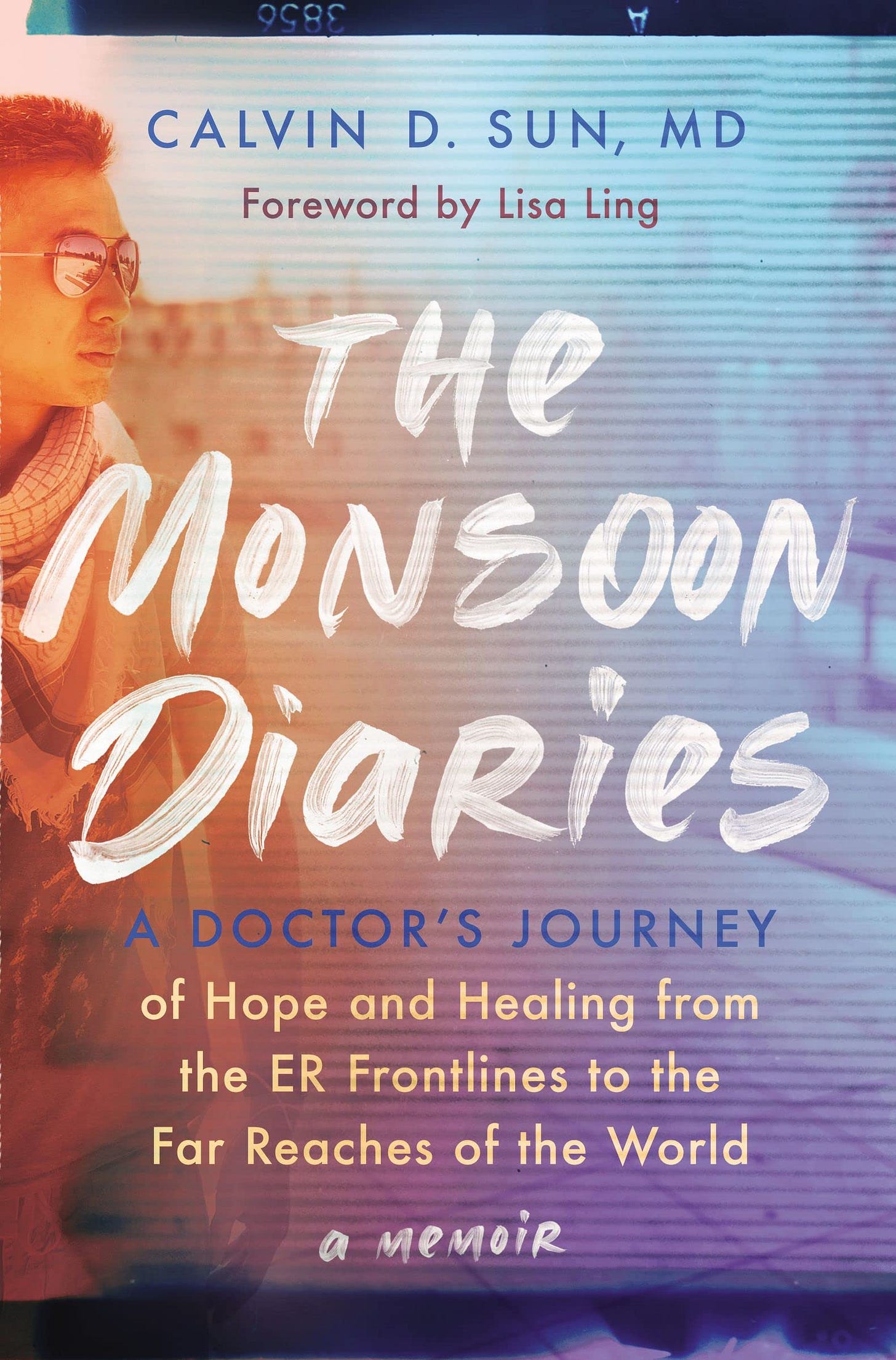

The Monsoon Diaries

New York Emergency Room Doctor Details the Reality of Early Covid in New Book, The Monsoon Diaries

Hi everyone, often we invite thought leaders to share their perspectives in and around AAPI culture. This week, we’re delighted to have Dr. Calvin Sun shares How He Learned to Live in the Moment While Fighting Covid in his new book, The Monsoon Diaries.

Dr. Calvin Sun worked in seven Emergency Rooms across four of the five New York City boroughs and recounts the early months of Covid in his new book, The Monsoon Diaries: A Doctor’s Journey of Hope and Healing from the ER Frontlines to the Far Reaches of the World. His on-air interviews, frequently from the ER, on NBC, MSNBC, FOX Business and CNN kept New Yorkers and all of America apprised of the raging pandemic.

Starting in early March 2020 through July, Dr. Sun chronicles the courageous efforts of frontline healthcare workers, risking their own lives as they fought to keep patients alive. With a foreword by CNN journalist Lisa Lang, The Monsoon Diaries details how the New York medical systems were woefully unprepared for the pandemic, struggling to make policies to protect the public and frontline heath care workers without sufficient PPE, ventilators, ICU beds or funding.

Dr. Sun shares his journey, from growing up as a young Asian American in New York, to the grief of losing his father as a teenager and his calling first to medical school and then to the open road. He weaves his love for travel into the memoir, sharing how a lost bet and a $600 flight to Egypt changed his life. Before the pandemic, Dr. Sun worked per diem, so his flexible work schedule allowed him to lead adventurous trip across the globe, averaging one international trip a month. He recorded his travel adventure on a blog title Monsoon Diaries, after traveling to Southeast Asia and India during Monsoon season. Today Dr. Sun has traveled to more than 200 countries and territories with over hundreds of companions from around the world.

We had a chance to chat with Calvin about his book and his experiences:

You worked per diem in numerous ERs across 4 out of the 5 boroughs of New York City, gaining a unique perspective of the pandemic unfolding in different environments compared to a full time doctor within a single hospital system. Can you share what March and April 2020 were like for you?

Calvin: As I wrote in my book, “what kind of nightmares would I still have if I weren’t already living in one?”: It was like running naked into a Category 5 Hurricane, while also being asked to board up everyone’s houses with no more wood left.

Because our patients were so vulnerable at a time when we felt similarly helpless and vulnerable, the line between patient and caregiver blurred and it felt like we all became sacrificial lambs to the pandemic. Not only were we both stuck on the frontlines facing a little-known virus that could potentially also harm our families at the time, we also had inadequate protective personal equipment and no idea how long this was going to last, when it was going to end, as well as knowing we would also be deprived of the resources that would recharge us and refill our cups during a lockdown.

We have come so far since March 2020, but Covid is still very much with us. What was it like to look back at those first few months and write your experiences?

Calvin: Cathartic: Writing is therapy. Revisiting and refacing difficult events, as hard as they may feel, is part of the healing process. This was mine.

And in turn with writing a book for others to read, we need to properly acknowledge what happened -- what we all went through together – as part of a collective healing process.

Knowing what was ahead for you, what would you tell March 2020 Calvin?

Calvin: Keep your head up. Keep writing. Keep sharing. The world deserves to know the truth.

PPE shortages were incredibly serious, and many (most?) hospitals did not have enough masks, gowns, face shields, etc. Can you tell us about your experience trying to protect yourself from exposure?

Calvin: Like MacGyver on steroids; we furiously cobbled together feeble medieval armor for 21st century warfare -- trash bags, masks flipped upside down, re-wearing single-use PPE for weeks … all the while knowing what we really needed (a PAPR or a Powered Air Purifying Respirator) would never be made available to us. Were we that expendable? And when the CDC printed official recommendations mentioning “scarves” and “bandanas” as a last resort, that’s when we felt a sense of total abandonment by the very institutions meant to keep us safe.

You also share that a lot of people donated PPE to you. What did those donations mean to you?

Calvin: I thank them explicitly not only in the book but extensively in the acknowledgments: They saved my life and so many others. I felt seen. The home front to the front lines; it seemed as if all of humanity began to work together when we realized long established institutions were not going to be enough to protect us.

Because you work per diem, you don’t have the support and stability of a full-time job. But it also means there isn’t an HR or communications department holding you back from talking with the media. How did you start doing national tv interviews during the pandemic? Why was it important for you to share your experiences on a national stage?

Calvin: They reached out of the blue to me! I’m not sure how they found me, whether it was from previous work with them covering my monsoon trips, the media coverage of my visit to North Korea in 2011, or from my social media. Regardless, I learned how small the world can be; one appearance could lead to countless more.

I said yes to all of them because it was important to inform everyone stuck at home in a lockdown what they were staying at home for -- preventing more victims of an invisible enemy -- and what horrors behind the walls of the emergency room they were protecting themselves and their loved ones from.

You write about treating a nurse for Covid who asked to be intubated after seeing her oxygen levels. She was dead two days later. How do you keep showing up for work after something like that?

Calvin: We go back in for the people next to us as well as ensuring that the sacrifices of our fallen colleagues would not be in vain. Because if we don’t show up, who else will? The healthcare system would have otherwise collapsed. As long as we kept showing up, we knew we were doing our best to hold the line.

Your grandfather called you with Covid symptoms in April and you advised him not to go to the ER, that you would come over and monitor him. But he called 911 anyway and went to the hospital. You monitored his care with the ER staff until his death on April 22, 2020. So many of us have lost loved ones to Covid. How did his death affect you?

Calvin: I felt so alone for him, how he must have felt dying alone, and then anger at myself for not doing enough. I also felt hopeless, helpless, aggrieved, and inconsequential. Meaninglessness. A void.

Then as I watched the pandemic progress to as far as California, I felt the same kind of inconsequential and wrote the following in the wake of processing his death a few months later:

“I’ve acknowledged the gratitude for at least still having the privilege and space of even processing these emotions. But daily expressions of gratitude cannot shield us from the frustration of seeing countless people like my grandfather having suffered unnecessarily, as well as a sense of indifference by the countless others who have chosen to ignore what’s going on.

While many of us have struggled to warn, protect, prevent — whether or not in vain — all the privilege in the world can’t heal helplessness. And yet this hidden force (Is it Privilege? Conscience? Karma? Self-Righteousness? God? Purpose? Empathy? Love? Habit?) remains, committing us to a responsibility where we may at least validate kindred peers out there who struggle alone in their grief. Perhaps if we could reach even one person, who then can help another loved one, entire communities and people like my grandfather can be protected.

I’ve been angry at myself and various people the past few years for many reasons, but I realize none of it may have been worth it. I instead now direct most of my rage at ages-old established institutions of socialized behaviors that have encouraged self-serving entitlement to eclipse compassion.

I don’t want this to be a self-righteous condemnation of anyone in particular — we’ve all been part of the problem. We’ve all stumbled and forgiven ourselves. But among my many imperfections as a human, I still strive for self-awareness, to learn, separate myself from my own bad habits, and at least not put anyone in harm’s way. I only wish the rest of my world could also collectively surrender a little entitlement and want the same. Only then can we stop perpetuating a vicious culture. So even as inconsequential as this post may be, may we continue to burn, burn, burn with rage rather than become indifferent. May we stay human.”

Your father’s death when you were a teenager must have been devastating. How did his death lead you to go to med school, which started as his idea more than yours?

Calvin: After the death of my father, I initially rejected medical school believing it was his dream for me to be a doctor, and not my own. However, after losing a bet that led me to travel internationally and realizing how little I knew about myself, something stirred within my subconscious: perhaps I was rejecting an idea -- an entire career in medicine -- because of him. What if I was actually meant to be a doctor all along, but instead I was about to live my entire life shutting down that possibility as an act of rebellion against my father without ever knowing? Or was this a sick version of reverse psychology emanating from his grave? Like the Iocane Powder "Battle of Wits" scene from the movie "The Princess Bride", I didn't know which of my thoughts was the poison, or ones I should trust.

In the end if I truly wanted to be free from his influence, I needed to decide for myself. But how? This mental jiu-jitsu frustrated me, so out of that psychological morass I said to hell with it and took concrete action, wagering another challenge to myself apply to medical school to see if I was even meant to get in. Just like losing the bet that would lead me to Egypt, the expectation was that I would get denied from every medical school, check that box off, and move on.

Although I had a sub-par collegiate GPA and poor test-taking skills, I worked hard on my personal statements and interviews; I definitely didn't half-ass anything and always have put my best foot forward. I relied on allies along the way who would believe in me more than I did as well as the detractors who motivated me to think differently; skepticism or support, I could not have gotten as far as I did without them. Nevertheless, just as I didn't expect myself to travel as much as I would until it happened, neither did I expect to get in anywhere. But one school found me “an interesting candidate" and wanted to take a chance on me: I got in.

And from medical school until working as a doctor in NYC Emergency Rooms during the pandemic, I would still spend half my time living a life in medicine, and the other half leading adventure trips around the world. Over the past 12 years, I’ve traveled to over 200 countries and territories, all while completing medical school and medical residency in Emergency Medicine. I am now grateful to share my origin story through the loss of my father and travel and how they both indirectly prepared me for my experiences in seven different Emergency Rooms during the early months of COVID-19, in my memoir, The Monsoon Diaries: A Doctor’s Journey of Hope and Healing from the ER Frontlines to the Far Reaches of the World.

Despite more than a few close calls and almost getting kicked out a handful of times along the way, I still became a doctor and now so grateful that I have become one – and grateful that I became a doctor not for the “destination” and end result but rather for the journey that got me here. And what a journey it has been; one I can gratefully claim as mine to tell.

What were the first signs that New York was coming through the crisis and was starting to heal?

Calvin: When people starting cussing at each other to put their masks on and the reply would be ironically thanking each other for the reminder.

Then as the weather warmed and Spring came amidst over weeks of daily city-wide rallies for BLM, our rates for COVID-19 related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths continued to drop. That’s when I realized COVID doesn’t spread well at all outdoors.

Between chapters explaining the realities of Covid, you share your love of traveling that started with a lost bet and a $600 flight to Egypt ten years go. Now you lead groups on trips across the world and refer to it as Monsooning. Why the name and why the wonderlust?

Calvin: I was enamored with how the weather pattern of a monsoon, as intense as it can be, tends to be positively reframed in many parts of the world as portending the harvest season. A monsoon also leaves as quickly as it arrives while still covering a large surface area in a short amount of time, and that’s how I like to travel.

It soon became synonymous with a style of travel that my co-travelers have considered unique for combining spontaneity and adventure without giving up your day job. Like those who spontaneously decided to run along with Forrest Gump, it seems that people joining along for “monsooning” spontaneously grew out of my blogging every day while on the road.

Your bio says you have visited 200 countries and territories. What’s not on that list? Where are you going next?

Calvin: A handful of island countries in the Pacific Ocean, Bhutan, Syria, and much of West and Central-East Africa. And if it’s not on that list, that’s where I’m going next!

The book ends with a cross-country road trip beginning in June 2020 which led to an even larger one in August 2020, the first major trip and monsoon you were able to lead for 6 months. Was the ability to travel again a relief to you?

Calvin: You have no idea.

What dreams would I still have if I weren’t already living one?

…

You can connect with Calvin at calvin@monsoondiaries.com or follow his journey on Instagram @monsoondiaries.

If you’d like to contribute a Cultural Perspectives guest post, please reach out! jd@crushingthemyth.com

And, please share if you enjoyed this week’s Cultural Perspectives post:

We appreciate you.

— JD, founder, Crushing The Myth